Home or Institution? Design Choices that Shape Belonging in Dorms, Care, and Transitional Housing

The first impression of a room can shape the whole experience of living there. We were excited about moving my son into his university dorm, ready to help him settle in and begin this new chapter. In the weeks before, I had searched online for move-in checklists and packing advice, and along the way came across articles about parents who went so far as to hire interior designers for dorm rooms. That seemed like overdoing it, and I was sure we would keep things simple.

When I moved into my own dorm decades earlier, I remember the excitement of stepping into a space that felt full of possibility. It was modest, but I was able to unpack, organize, and display personal objects right away. That small sense of ownership helped the room feel like mine almost immediately. My son’s experience could not have been more different. The moment we opened the door, his excitement quickly faded as he took in the starkness of the space: bare walls, peeling paint, harsh fluorescent lighting, and almost no natural light. The closet was no better, with an unnecessary swinging door jammed inside sliding panels and a clothing rod that collapsed under the weight of his clothes. While I tried to stay encouraging, inside I worried about the effect such an unwelcoming environment might have on his first year away from home. He summed it up in a single phrase: it felt like a prison cell.

My son's drab and impersonal dorm room.

The more functional side of the closet, supplemented with purchased temporary storage

The bleakness extended beyond the room itself. The narrow double-loaded corridors were lined with flickering fluorescent lights, bare walls, and linoleum floors, forming square loops where each corner looked exactly the same. Every door was identical, so the only way students could tell which room was theirs was by the temporary sticker with their name on it. It was monotonous, disorienting, and unwelcoming, more institutional than residential.

Long, institutional corridors with flooring that produces glare, reinforcing an unwelcoming atmosphere.

In that moment, I suddenly understood the temptation behind those stories of parents splurging on dorm room makeovers. Faced with such a bleak space, the urge to make it feel warm and livable seemed necessary, especially as a parent concerned for a student’s well-being during the transition to college.

What struck me most was how unthoughtful the environment was. Instead of encouraging comfort, autonomy, and a sense of ownership, the room created barriers. Strict dorm rules only added to the problem: no nails, no adhesives, just sticky white tack that cannot hold anything substantial and ruins whatever it touches. These policies aimed to keep walls pristine for the institution, strip away opportunities for students to personalize their space and make it their own. With no drawers and only one closet shelf, students turn to makeshift storage that is costly, short-lived, and wasteful. Each year the cycle repeats, with boxes and storage items piling up in dumpsters at move-in and move-out. It is a missed opportunity for sustainability and dignity, when dorm rooms could instead be designed as turn-key spaces that welcome students, respect their needs, and stand the test of time.

From a design perspective, this is not a trivial detail. A room like this does not support well-being, identity, or placemaking. It feels sterile and institutional rather than homelike. For a young person just starting out, that difference can make or break the experience. With more thoughtful design, dorms could shift from places that heighten stress and isolation to spaces that foster comfort, autonomy, and belonging, giving students a stronger foundation for success. Natural light and a view of nature can help regulate circadian rhythm and provide a sense of restoration. Adequate storage and clear organization reduce stress and make it easier to focus on studies. Even modest improvements, such as these, can transform dorms from temporary holding spaces into environments that support growth and well-being.

Above-bed shelving combines convenience with opportunity to personalize. RVC, 1990.

Bleak dorm room with no shelving or supplied bedside table, leaving students to find their own solutions.

The kinds of improvements that would make dorm rooms more supportive align closely with the Environmental Audit Scoring Evaluation (EASE),¹ a tool developed to guide person-centered design in senior care environments. Many of the elements EASE measures are just as important for college students as they are for older adults. EASE highlights the value of spaces that allow personalization, provide adequate light and orientation cues, and are organized to reduce stress. Dorm rooms, like senior living apartments, benefit from built-in supports for personalization such as shelves, cork boards, or picture rails. Picture rails, once common in older buildings, are especially well suited to these settings. They protect walls while giving residents freedom to hang photos, artwork, or objects that make a space feel like home. Lighting should be flexible and residential in character, with dimmable options instead of a single fluorescent fixture. Corridors should avoid long, monotonous stretches by grouping rooms into smaller clusters and adding distinctive features, helping orientation and making the environment feel more human-scaled. Even small touches, like a hook on each door for decorations or a ledge to display something personal, can go a long way toward creating a sense of belonging.

Imagine if dorms and care communities alike were designed with these principles in mind. Instead of sterile, institutional settings, we would have places that foster comfort, autonomy, and belonging, environments that support dignity and personalization across all stages of life

Built-in desk and cabinetry allow for personalization and storage. RVC 1990.

Me moving into RVC in 1990. I clearly felt welcome in this space.

The more thoughtful design of my own university dorm, built in 1965, has endured for nearly sixty years. The built-in cabinets looked dated when I lived there in 1990 and still do today, yet they have a certain classic character, and the history of the building only adds to their meaning. The abundant built-in storage continues to function well, making it easy to unpack, organize, and display personal belongings. Just as important, it signals that thought and care were given to the needs of the inhabitant, a small but powerful way of saying that they are welcome. The corridor formed a loop, but the stretches were shorter and punctuated with turns. Unlike my son’s linoleum hallways, ours were carpeted, which not only softened the acoustics but also encouraged students to gather. We spent hours sitting together on that carpet, talking and studying. Even the bathroom, tucked in the middle with doors on either side, became a meeting place as people passed through. It was not luxurious, but it was thoughtfully designed, and that thoughtfulness has given the building staying power.

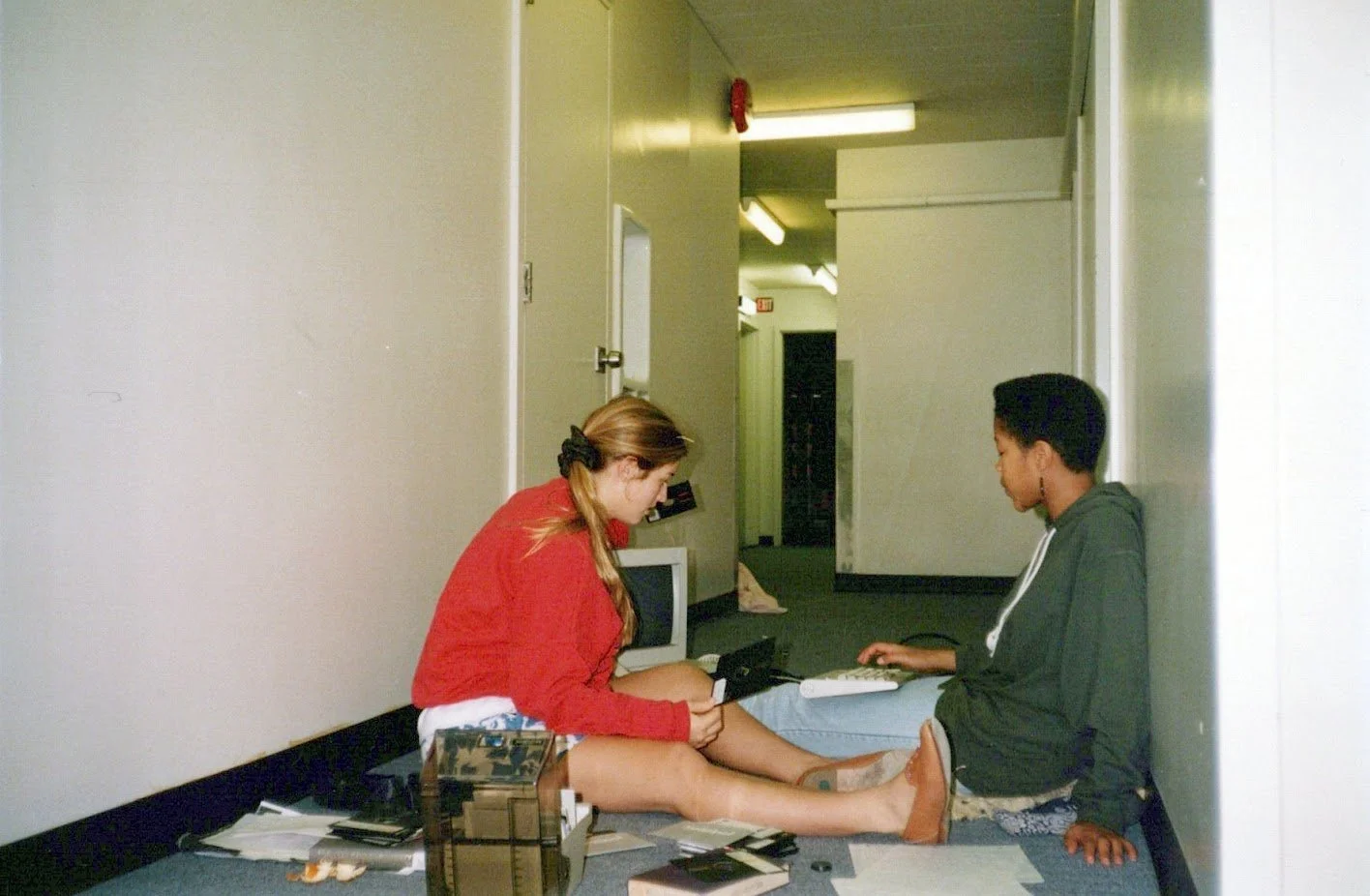

The design of shorter, grouped hallways at RVC, circa 1990, made corridor hangouts a natural gathering place.

Studying in the hallway at RVC,1990. Though drab, the carpet and shorter hallways make the corridors feel more homelike.

Whether for students just leaving home, families in transitional housing, or older adults entering long-term care, the need is the same. Dignity and personalization are universal design needs. Buildings that are thoughtfully designed and built to last convey pride of place, and that pride extends to the people who live there. A dormitory or care community that respects its own history and character signals respect for the individuals inside. Too often, temporary housing is designed for turnover rather than longevity, and residents feel that lack of care. But when a building shows respect, through durability, personalization, and attention to detail, people are more likely to feel valued, to care for the space, and to see it as their own.

Environments shape experience, and thoughtful design can either undermine or strengthen well-being. It is time we invest in housing, from dormitories to transitional housing to senior living, that balances durability and cost without stripping away the very things that make us feel welcome and at home.

REFERENCES:

Wrublowsky, R. A., Calkins, M. P., & Kaup M. L. (2023) Environmental Audit Scoring Evaluation: Training Manual. Produced by RAW Consulting and IDEAS Institute

https://people.com/college-dorm-room-makeovers-have-gone-too-far-11798617

https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2025/08/college-dorm-decor-intensive-parenting/684001/

https://parentscanada.com/opinion/forget-designer-dorm-rooms/