Breakrooms in Long-Term Care: What Staff Say They Need

In long-term care communities, much attention is given to designing environments that feel like home for residents. Yet the same level of care is rarely extended to those who provide the care. In a recent study I conducted involving staff breakrooms across six long-term care communities in the Pacific Northwest, staff consistently noted the lack of comfortable and functional places to rest. Breakrooms often lacked privacy, felt too close to the care environment, and did not offer the kind of separation caregivers needed during their shifts.

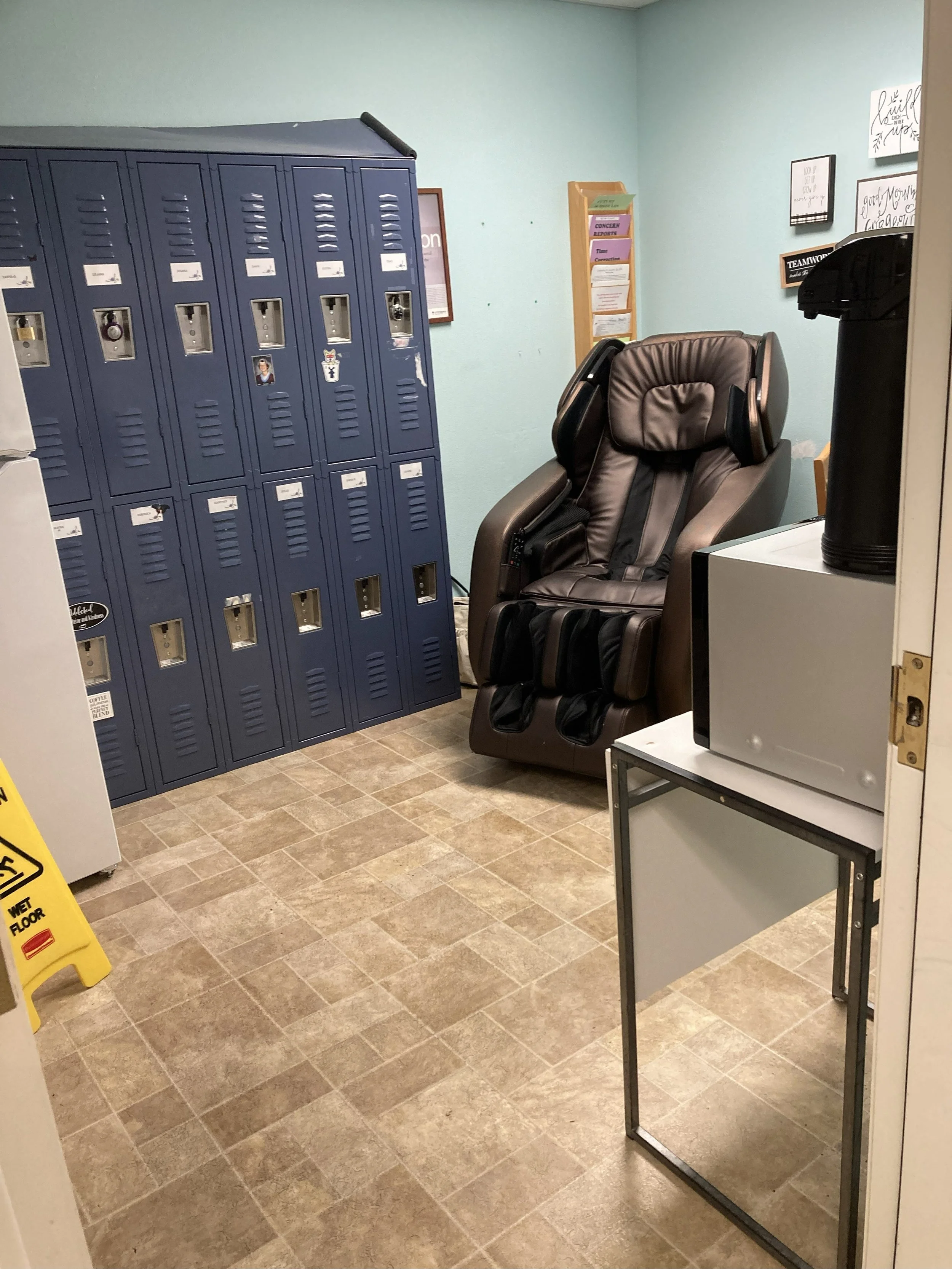

Some staff valued the massage chair, but many noted that the breakroom was too small, did not offer enough seating, and felt too depressing. More than half said they would use the space more often if it had a window. Image by author.

Findings from the Field

In the survey, staff said they did not use the breakroom every shift, but on average they used it a little more than sometimes. Across the six communities assessed, only one breakroom contained all the features required for a full score on the Environmental Audit Scoring Evaluation (EASE), an evidence-based design tool that evaluates how well the physical environment supports both caregiving and resident-centered practices¹. These features include being located close to the living areas where caregivers work, providing large windows and pleasant lighting, offering comfortable furniture and some kitchen or vending amenities, and having direct access to an outdoor space.

But how do we determine what is too far? When staff were asked why they did not use their breakrooms, 37 percent said the rooms were too far from where they worked. In one community, the breakroom met all the recommended features for a staff retreat, and it was used more often than the other breakrooms. Yet 44 percent of staff in that same community still felt it was too far. Because EASE does not define what distance counts as close to the living areas, this part of the assessment is subjective. The findings show that a breakroom can be perceived as far but still be chosen more often when other qualities make it appealing.

A high scoring breakroom with outdoor access, natural light, and comfortable seating, but privacy is still limited. An adjacent anteroom holds lockers and posted notices, just out of frame. Image by author.

At the same time, being physically close does not always make a breakroom more usable. In another community, the breakroom was a separate room within the care space, but a caregiver said they left the building for breaks because they could not fully disconnect. Colleagues would come to the door with questions or requests, and the sound of call bells, pagers, and doorbells carried into the room. Having been called back to work during breaks in the past, they preferred to step outside the building to achieve a true sense of separation.

Crowded storage blurs the purpose of this breakroom, making it feel like an extension of the work area rather than a place to recharge. Even with natural light and comfortable seating, the lack of privacy limits its restorative potential. Image by author.

Taken together, these examples suggest that staff want a breakroom that is close enough to reach easily but offstage enough to feel separate from caregiving. Proximity helps only when paired with privacy, acoustic separation, and relief from the constant cues of work.

The massage chair signals relaxation, but the utility of the environment does not. Lockers and posted signs add visual clutter and work reminders that compete with the room’s purpose. Image by author.

Lack of privacy was also a strong deterrent. Thirty-six percent of surveyed staff cited privacy concerns as a reason they did not use the breakroom. None of the observed breakrooms offered true privacy, and many caregivers sought alternative spaces such as their cars, the salon, their desks, or stairwells for decompression. For some, these quieter locations were the only places they felt comfortable calling family or taking care of personal calls and tasks during the workday. Supporting staff in managing these responsibilities may ease day-to-day stress and, in some cases, help reduce avoidable sick days.

Thirty-one percent of staff said they would like a private outdoor area, reinforcing the need for both physical and psychological distance from care environments during breaks. Keeping lockers and posted notices out of the breakroom also matters, since work reminders and visual clutter can make the room feel less restorative and more like an extension of the care environment.

Even during breaks, staff are met with work notices, reinforcing that the space is not fully separate from the care environment. However, this space does have natural light and views of nature. Image by author.

Other barriers included breakrooms described as too depressing (30 percent), not having enough seating (28 percent), or having uncomfortable seating (27 percent). Twenty-four percent said they rarely had time for a break, while others preferred going outside or noted limited amenities. In communities whose breakrooms lacked windows, nearly half of staff said they would be more likely to use the space if natural light were available.

These findings mirror earlier research. Nejati et al. (2015) found that restorative break areas are used more often when they are close to work areas, provide privacy, and offer access to outdoor spaces².

Design Recommendations

The study offered practical, evidence-based guidance for improving staff recovery:

Create breakrooms that are outside the care space but still close enough for staff to reach during short breaks. Staff prefer a sense of separation combined with easy access.

Provide acoustic and visual privacy so caregivers can truly step away.

Include windows and natural light, calming aesthetics, and comfortable seating options.

Offer access to a small outdoor area for quiet time or fresh air. Even brief exposure to nature supports restoration, and earlier research has shown that outdoor spaces offer greater restorative potential than indoor views alone².

Ensure the breakroom has basic kitchen or vending amenities and a firm surface for resting backs.

Keep notices and equipment storage out of the breakroom so the space signals rest rather than work.

Place staff lockers outside the breakroom but still nearby for convenience. Lockers and posted notices can be grouped in a small anteroom or alcove rather than inside the restorative space. This keeps work reminders, visual clutter, and posted schedules out of the breakroom and supports a calmer, more restorative environment.

Staff emphasized that being able to step away, even briefly, to a calm and private environment makes their work more sustainable. When caregivers can recharge, they return to their residents more focused and grounded, which benefits the entire care community.

References

Wrublowsky, R. A., Calkins, M. P., and Kaup, M. L. (2023). Environmental Audit Scoring Evaluation: Training Manual. RAW Consulting and IDEAS Institute. Available at www.SAGEFederation.org/EASE.

Nejati, A., Shepley, M., Rodiek, S., Lee, C., and Varni, J. (2015). Restorative Design Features for Hospital Staff Break Areas: A Multi-Method Study. HERD: Health Environments Research and Design Journal, 9(2), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586715592632